The Kasimir Fajans papers at the Bentley Historical Library informed and inspired this article. Other sources include Kasimir Fajans (1887-1975): The Man and His Work, and Bulletin of Historical Chemistry, 1989/1990.

Nothing, not even the breakout of World War I, seemed to be able to interrupt the research of chemistry professor Kasimir Fajans.

Despite being a Polish-born Russian citizen working in Germany, Fajans had only to check in each morning to the local police station to be allowed to continue his work while the European continent was embroiled in bloody conflict. It was as if being on the cutting edge of radioactive and physical chemistry made him immune to the effects of war and politics.

This charmed state continued until the rise of Adolf Hitler and the Third Reich in 1933. The pall of Nazism could not be ignored.

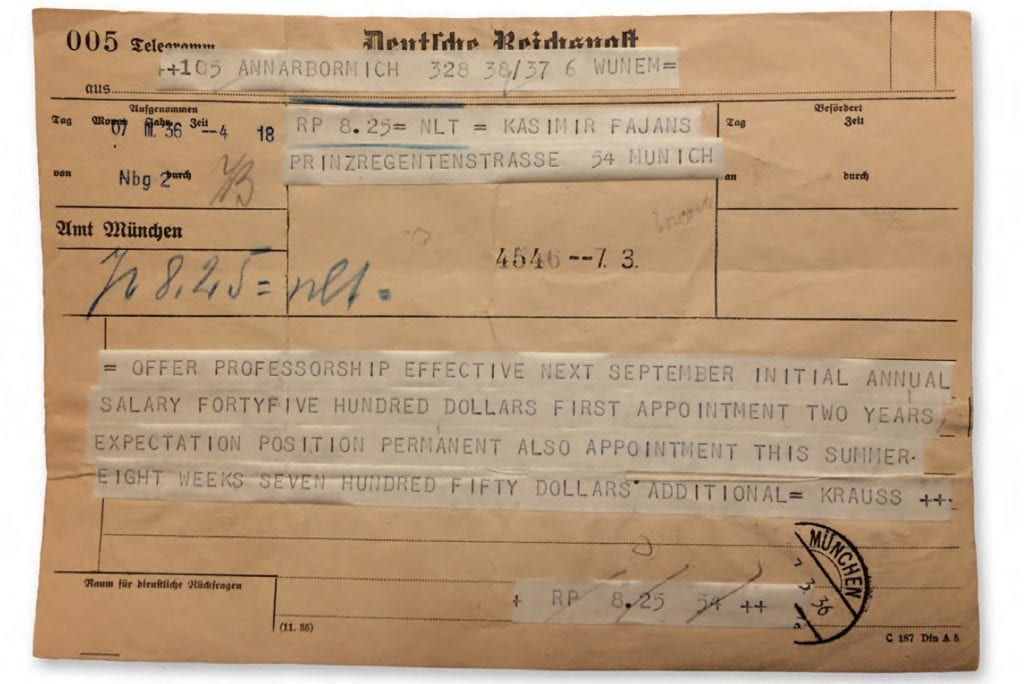

Fajans, who was of Jewish decent, found himself abandoning the work of a lifetime in order to flee to England. One of the greatest minds in chemistry was out of work and on the run at the dawn of the atomic age. Or he was, until he received a lifeline from across the Atlantic, in the form of a telegram from Edward Kraus, Dean of the College of Literature, Science, and the Arts at the University of Michigan.

Kraus had heard of Fajans’s plight and wished to extend an offer of professorship of physical chemistry at the University. Fajans would bring prestige and an outside perspective to U-M’s then insular chemistry department. Time was of the essence for Kraus, who wanted to secure Fajans before other American universities could extend competing offers. The medium of telegraph messaging left little room for nuance:

“OFFER PROFESSORSHIP EFFECTIVE NEXT SEPTEMBER INITIAL ANNUAL SALARY FORTYFIVE HUNDRED DOLLARS FIRST APPOINTMENT TWO YEARS EXPECTATION POSITION PERMANENT”

The Persecution of a Genius

When Fajans was born in Warsaw in 1887, Poland was under the thumb of the Russian Federation. Being a native Pole of Jewish ancestry effectively barred him from entry to his homeland’s best universities.

Fajans left his home country to study biology at the University of Leipzig in Germany before receiving his Ph.D. in chemistry at the University of Heidelberg in 1909. He thrived in his new environment, discovering a passion for the emerging science of physical chemistry.

Fajans’s postgraduate career began with a fellowship in the laboratory of Nobel laureate Ernst

Rutherford in Manchester, England. Shortly afterwards, he moved back to Germany to accept a position at the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology, where he came up with his soon-to-be-famous “Displacement Laws of Radioactive Decay” theory. Fajans and his colleague Fredrick Soddy were the first to describe in detail the process of an atom that is changing due to radioactivity.

More profound success soon followed. While studying the radioactive decay of uranium, Fajans and his colleague Otto Göhring discovered a new element—a supreme achievement for any chemist. This finding was even more impressive due to the fleeting nature of the new substance: its half-life was a scant 1.17 minutes. Because of this ephemerality, Fajans and Göhring named the element brevium. Although they received many accolades for the breakthrough, they were stripped of the title of discoverer when another pair of scientists found a more stable form of the element five years later. The name was changed from brevium to protactinium.

Nonetheless, news of Fajans’s work made its way across the Atlantic. In 1930, Cornell University sponsored a lecture tour for Fajans. He traveled to campuses across the United States, including his first trip to Ann Arbor. The Rockefeller Foundation, a philanthropic group from New York, was so impressed with Fajans that it recruited him to head its new Institute of Physical Chemistry in Munich.

Shortly after his return to Germany in 1932, everything Fajans had been working for came crashing down. Hitler had lost the 1932 presidential election but was still a rising political star, with the Nazis winning more than 200 seats in the German Reichstag (parliament) that year. Meanwhile, the Nazi Storm Troopers, Hitler’s army of brown shirts, used intimidation and violence against political adversaries and cultural groups, suppressing Hitler’s opposition and spreading terror. In 1933, Hitler was appointed chancellor of Germany and, by 1934, he was Germany’s president.

Fajans (left) and Dean of LSA Edward Kraus (right) at Kraus’s Ann Arbor home in 1948.

At first, Fajans was able to operate under the newly formed Nazi government. His connection with the powerful Rockefeller Foundation gave him relative autonomy while other German universities were made to fire their Jewish professors and change their curricula to align more closely with Nazi principles. Soon, however, conditions in Germany made it impossible for Fajans to recruit new students or faculty. Rumors of kidnappings—or worse—of Jewish colleagues settled Fajans’s mind on abandoning the institute and the fruits of two decades of research.

It was while packing for his exodus from Munich that Fajans received the telegram from Kraus in the United States via his eldest son, Edgar, who was living in England.

A Michigan Legacy

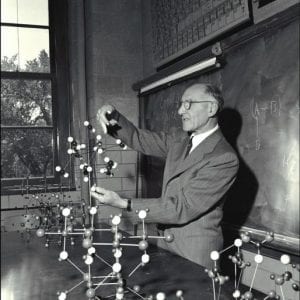

Fajans stayed at Michigan until his retirement in 1957. His work on radioactive decay made many of his colleagues believe he would win the Nobel Prize in chemistry, but it was not to be. The window for Fajans to have won the award may have been during the three years the Nobel was suspended because of World War II.

In 1992, the Regents of the University of Michigan established the Kasimir Fajans Professor of Chemistry, Physics, and Applied Physics. Today, the position is held by Department of Chemistry Professor Raoul Kopelman, who runs a campus lab with more than 15 active researchers in the areas of analytical chemistry, physical chemistry, biophysics, and applied physics.