In the spring of 1933, Arnold Gingrich, a publishing entrepreneur not yet 30 years old, was starting a magazine that nobody thought could succeed, certainly not in the deepest pit of the Great Depression.

It was to be a fashion magazine for men. The idea had a scent of “lavender,” people said—a euphemistic way of saying only homosexual men would read about fashion. The working title, which no one loved, was Esquire.

But men’s clothiers were begging for printed material to give or sell their customers. Gingrich and his partners figured if they could sell the magazine to men’s stores in advance of printing, it might work — if they bulked up the fashion content with overtly manly fare. They jotted notes about ideal articles: “Bobby Jones on Golf, Gene Tunney on Boxing, Hemingway on Fishing.”

By Ernest Hemingway. That byline alone could convince male consumers of a publication’s masculinity. The novelist was nearly as famous for his obsessions with fishing, hunting, and bullfighting as he was for his literature.

So Gingrich pitched Hemingway. To the young editor’s delight, the celebrity novelist said yes.

Thus began a relationship that would thrive for several years in Hemingway’s prime, and the writer’s reputation helped Esquire become a leading magazine.

Copies of his letters are among the highlights of Gingrich’s personal papers, which the editor’s heirs gave to the Bentley Historical Library in 1976. (The original letters are archived at the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library in Boston.) The gift memorializes Gingrich’s student days at the University of Michigan from 1921 to 1925. The Bentley also has the full records of Esquire, Inc., containing correspondence, manuscripts, and letters from many more authors.

The Gingrich papers reveal a side of Hemingway seldom mentioned in English courses—the canny careerist behind the gifted artist. There are lessons here for anyone who seeks not just to produce distinguished work but to make a living at it.

Do Not Count Anything

The two men happened to meet in a New York book shop. Gingrich had his opening to pitch his fledgling magazine to Hemingway.

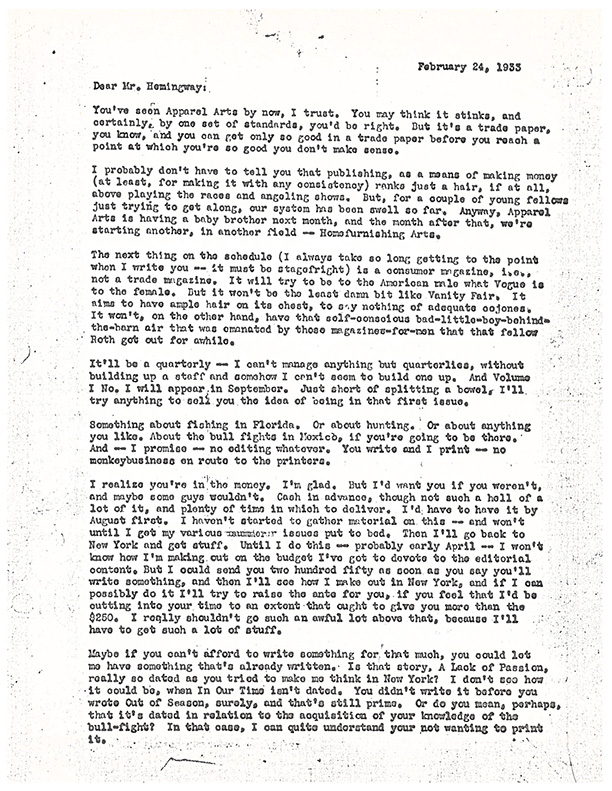

“It will try to be to the American male what Vogue is to the female,” he wrote to Hemingway after their initial encounter. “It aims to have ample hair on its chest, to say nothing of adequate cojones.

“Just short of splitting a bowel, I’ll try anything to sell you the idea of being in that first issue. Something about fishing in Florida. Or about hunting. Or about anything you like …. And — I promise — no editing whatever. You write and I print — no monkey business en route to the printers.”

The catch was the low fee: $250 per article. By Hemingway’s standards, that was loose change. But the writer liked Gingrich. “You write a very good letter,” he replied. For a nonprofit publication he charged nothing at all, he said, but for a commercial publication, he demanded “the top rate they have ever paid anybody. This makes them love and appreciate your stuff and realize what a fine writer you are.”

For Gingrich he made an exception. He was about to go fishing off Cuba. “If I get suddenly flat and need 250 dollars,” he might knock out a piece for Esquire. “But do not count on anything.”

Gingrich coaxed Hemingway along, praising his work and even sending him a nice suit. (He had great connections in the clothing trade.) Hemingway promised to write one “letter” (his term for a casual piece of first-person nonfiction) for each of Gingrich’s first year of quarterly issues. “You send me the first 250 when I write for it and so on. Getting the money will make me write the piece.”

It’s not clear why he agreed to such a low fee. Whatever the reason, he asked Gingrich to keep it secret.

“Writers get paid by a certain category—i.e. what they can get—it is a racket controlled by supply and demand. I would rather write for nothing if I had any way of living or enough cash otherwise. Because I haven’t I have to keep the category that I have and charge them plenty …. But if you tell anyone I wrote you pieces for 250 it would cost me 2500 a piece ….”

Gingrich's first letter to Hemingway in 1933 asking him to write for Esquire magazine. Arnold Gingrich Collection, Box 1

An Eye on Business

In handwriting or typewriting, Hemingway’s letters tumble like boulders from clause to clause, topic to topic, through thickets of punctuation.

He reported on his opinions of other writers (Gertrude Stein “was a damned pleasant woman before she had the menopause”); his fishing expeditions (“ … caught 3 bonita, a mackerel, two big barracuda …”); his health (“Now have an infected right finger … hurts like holy bloody hell”); and his productivity.

“Finished the long book [Green Hills of Africa] this morn-ing, 492 pages of my handwriting,” he wrote from Key West in 1934. “Going to start a story tomorrow. Might as well take advantage of a belle epoque while I’m in one.”

But he also kept a close eye on business. When Gingrich invited him to go on a first-name basis, the writer said: “I’ll drop the Mr. if it means anything to you,” but only with reservations. “In dealing with anyone in business when you become pals they can always invoke the necessities of business versus your own needs” — thus “the proffessional’s [sic] reluctance to become a friend to either his employer or his audience.”

Hemingway got Gingrich to advance him $3,000 against future articles so he could buy a 38-foot fishing boat. He promised that he, or his estate, would be good for the money. “If I bump off … owing you money my wife will pay you what is due i.e. if I have written eight articles and owe you two … she will send you check for 500 at same time as paying undertaker.”

Wary Friends

Gradually the relationship tilted toward friendship — the kind that executives might cultivate on a golf course, liking each other but watching for opportunity.

Before long, Hemingway invited Gingrich to come south for some deep-sea fishing. The novelist John Dos Passos, a pal of Hemingway, came along. Watching the two, Dos Passos saw “Papa” capitalize on the junior partner’s hero-worship.“It was as much fun to see Ernest play an editor as to see him play a marlin,” Dos Passos recalled. “The man never took his fascinated eyes off Old Hem …. Sure he would print anything Hemingway cared to let him have at a thousand dollars a whack.”

But who had played whom? Gingrich had been savvy, too. It was he who had induced a world-famous writer to lend his byline to a start-up magazine at a deep discount—quite possibly the leading factor in Esquire’s early success, since Hemingway herded other big names, including F. Scott Fitzgerald, Ring Lardner, and Dos Passos himself, into Gingrich’s stable.

Hemingway’s generosity fully emerged when Gingrich sought his advice on writing.

The editor, a bear for work, had written a novel in his spare time, and the early draft was good enough to earn a contract from Alfred A. Knopf, a prestigious publisher.

Hemingway warned Gingrich about the danger of splitting his time between writing and business.

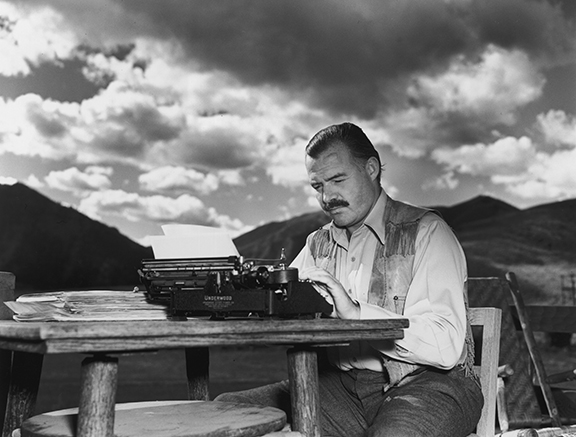

Hemingway with his typewriter in Idaho, 1939. Lloyd Arnold /Hulton Archive/Getty Images /

“You have this ungodly amount of drive and energy …,” he wrote Gingrich, “but no matter how good a paragraph it would make for your obituary how you ran this mag days and wrote a novel nights … that is not the way to write a novel. Writing a novel is such hard work that it is a full time job.

“The real secret in writing a novel is to keep inside of your action all the time like a horse. Don’t let the damned horse run away on you when you are going to have to keep racing him forever. And always stop at an interesting place when you still know what is going to happen. Then you can go on from there the next day and the next and etc …. Do a certain amount every day or every two days and always stop where it is interesting and while you are going good.”

When Gingrich defended the draft of his second novel against one of Hemingway’s critiques, the pro took the amateur to school.

“You’ve gotten yourself into a hell of a state about this book Arnold,” he lectured. He cautioned Gingrich against getting too attached to his words. “Goddamn it if you start defending what you write instead of attacking it to yourself and trying to beat it or better it or get rid of it you make yourself into an amateur.” He told the young writer that words couldn’t just mean something to the writer, they had to mean something to the reader, too. And that an amateur wouldn’t know the difference. “You want to split yourself into two people—the one that is to receive and the one that is to give. An amateur never can cut anything out or change anything radically Because He Wrote It.”

Postscript

In the summer of 1936, deep into drafting a new novel, Hemingway begged off his commitment to Esquire.

“It is practically a sin against the holy ghost for me to interrupt writing the novel at this point to write a [journalistic] piece or a [short] story,” he told Gingrich. “If I don’t give it every bit of juice I have … I’m a son of a bitch …

“I feel goddamned bad about this Arnold …. I think of you as the best and most loyal friend I have and the one guy who knows what I am trying to do. By staying out of the magazine now I am probably f—ing up my commercial career as badly as I f—ed up my critical status (the hell with it) by staying in it. But I haven’t any choice as long as I am working on this.”

Hemingway was writing To Have and Have Not (1937), parts of which drew a thin veil of fiction over the real-life marriage of the millionaire-executive G. Grant Mason and his socialite-sports-woman wife, Jane Kendall Mason. Hemingway had been conducting an affair with Mrs. Mason whenever he was in Cuba, where her husband was running Pan American Airlines.

When Gingrich urged Hemingway to soften the novel’s hard edge in order to avoid a libel suit, the two argued, and that was the end of the friendship.

It was complicated. Gingrich and Jane Mason married in 1940.

When one of Hemingway’s sons asked why he had suddenly stopped writing for Gingrich, the novelist said the former friends had “disagreed about a blonde.”

# # #

Hemingway’s letters to Arnold Gingrich fill several folders in the 25 boxes of Gingrich papers at the Bentley Historical Library. This collection is open to the public.

Additional sources for this story: Scott Donaldson, By Force of Will: The Life and Art of Ernest Hemingway (2015); Bernice Kert, “Jane Mason and Ernest Hemingway: A Biographer Reviews Her Notes,” Hemingway Review, 21:2 (Spring 2002); Arnold Gingrich, Nothing But People: The Early Days at Esquire (1971); and Hugh Merrill, Esky: The Early Years at Esquire (1995).