Ann Arbor resident Marjorie Franklin was thrilled when she learned she had been accepted into the U-M Hospital School for Nurses in 1924. First-year nurses had to furnish their own uniforms, but all else was provided, including housing in the nurses’ dormitory, board, and laundry. But when Franklin and her mother, Beulah Jones, went to meet with the Director of Nursing, they were informed that that there was “no housing provided for colored students.” Instead, she was encouraged to live at home.

Franklin and her mother persisted. In a meeting with acting Hospital Director Robert Greve, Jones was advised that “serious objections might be raised” by other students if Franklin were allowed to live in a dormitory. She was told that if there were “perhaps five or six colored girls,” then the University “would be glad to establish a separate nurses’ home for them,” but that doing so for a single student could not be justified. An offer was eventually made to reimburse Franklin’s off-campus housing expenses while extending her all other privileges, “dining room included, just as any other nurse would have.”

Franklin and her mother remained resolute and brought the matter to the attention of President Marion Burton, who was reluctant to take a position. Jones noted Burton “couldn’t see any possible way to put a colored woman in the dormitory,” though he wouldn’t go so far as to say it was impossible.

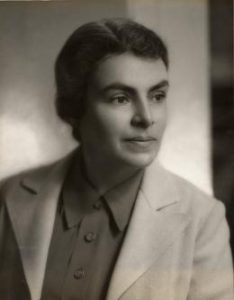

Marjorie Franklin, along with her mother, Beulah Jones, fought to be housed in the U-M nurse’s dormitory with the rest of her nursing cohort.

In October 1924, soon after her meeting with Burton, Jones wrote an impassioned letter to Frederic Williams, the president of the Detroit branch of the NAACP, presenting the facts of the case and describing the discrimination she experienced as “an unwritten law stronger than any law on the books.” Jones was emphatic that the only thing she would accept for her daughter was “absolute equality under the law.”

Bay City attorney Oscar Baker, a 1902 graduate of Michigan’s Law School, signed on as legal counsel for Franklin. Baker wrote to the directors of nursing and the University Hospital saying that, as a proud alumnus, “loyalty to my own group (colored)” far “transcends my loyalty to the University.” He asserted that the discrimination practiced by the University not only violated the law by failing to provide “full and equal accommodations,” but it should cause “any fair-minded alumnus” to “bow his head in shame.”

The issue went before the Board of Regents in 1925 at its May meeting. The Regents, however, were reluctant to intervene and settled on a carefully worded resolution stating that the “Franklin case presents a routine departmental matter” that did not require regental intervention.

A couple of months later, in a letter from hospital Director Harley Haynes to acting President Alfred H. Lloyd, Haynes conveyed the University lawyer’s opinion that the case was unwinnable and it “would be advisable to arrange for living quarters for Miss Franklin without taking the matter to court.” Against such an indefensible position, Haynes wrote to Baker informing him that as soon as the new residence hall for nurses was completed—Couzens Hall—Franklin would be housed there. African American newspapers hailed the victory.

Franklin’s case was settled. Nonetheless, the University’s larger responsibility for housing African American women remained unresolved.

"Not Enough Has Been Done"

Franklin’s journey is a noteworthy chapter in the history of equal-housing efforts at U-M. A similar struggle would begin for other African American women on campus just a few years later, while the push for full housing equality would continue through the decades that followed.

In 1927, the University of Michigan was badly in need of dorms for all women. The Martha Cook Dormitory and Helen Newberry Residence had opened in 1915, providing housing for about 200 women. In 1921, the Betsy Barbour Residence added 80 more spaces. Alumnae House and Adelia Cheever House offered rooms for a few dozen more. But the remainder of the women—some 1,500—lived in sorority houses or in the dozens of rooming houses that surrounded campus, including 76 League houses for women approved and inspected by the Dean of Women.

Also in the late 1920s, the president of the Michigan State Association of Colored Women, Christine S. Smith, was pushing hard for improved housing for Michigan’s African American women students dispersed across several private homes.

President C.C. Little wrote to Smith in 1928: “I think we both agree that not enough has been done in the past,” adding that the University was “eager to have the situation improved for these girls.” Little asked Dean of Women Alice Lloyd to take the lead.

Alice Lloyd, Dean of Women.

A private house at 144 Hill Street operated by Mrs. Esther M. Dickson, an African American widow, provided a quick and ready solution. Dickson wanted to switch from boarding male students to boarding females. Her house was quickly inspected and listed as an approved “League house for colored women” for the 1928-1929 academic year.

The house at 144 Hill Street proved unpopular. It was located far west of campus and near an active railroad track. The house also came under fire from members of the local African American community, including the Federated Association of Colored Women, which accused the University of segregation. Alice Lloyd’s annual report for 1928-1929 devoted much attention to the house for “colored women”; in response to the segregation charge, Lloyd resorted to legalistic hairsplitting, stating that her office “did not say at any time that the house was for colored girls only, but that colored girls would be welcomed.” Some African Americans saw the effort to create a separate house as a dodge by the University in order to avoid having to directly address the issue of admitting African American women into the dormitories, particularly with Mosher-Jordan about to open.

In April 1929, the Regents received a communication from Alice Lloyd and Ellen Stevenson, an instructor in geology and housing adviser, acknowledging the shortcomings of the Hill Street location. They recommended a house “at the edge of the colored section” on the southeast corner of Glen and East Ann. (Ann Arbor’s “colored section” was in the Old Fourth Ward, an area north of campus roughly bounded by Glen Avenue, Fifth Avenue, Huron Street, and the Huron River.)

The house at 1102 East Ann Street was located at the intersection of Ann and Glen streets and can be seen in the center of this photo taken in 1936.

The house at 1102 East Ann Street had been owned by the University since 1909. Alice Lloyd wrote, “if we can anticipate the problem of colored girls in the new dormitory before such dormitory is erected,” then a “very acute situation will be forestalled.” With the blessing of President Little, Secretary Shirley W. Smith, and Regents Junius Beal and James Murfin, the plan was approved. The sum of $3,500 was provided to add and equip a kitchen and dining room to serve meals and to furnish the study and living room. An additional $17,500 was appropriated to secure a new residence for the hospital maids who were occupying the house. Alice Lloyd added the belief that the house “will satisfy the colored girls and the Federated Association of Colored Women.”

The two-story frame house on East Ann was not a particularly attractive property. In 1913, when the University wanted to install a railroad spur to deliver coal to the central power plant, it acquired several parcels of land, including the adjacent three-story house at 1108 East Ann. In order to accommodate the railroad track, the house at 1108 was moved west, and physically conjoined with the house at 1102, creating a single large boarding house capable of housing up to 20 people. With a railway cutting through the backyard, it was not an especially desirable location, but some tried to put the best possible spin on it, including Alice Lloyd. She boasted in her annual report for 1931-1932 that “colored women were for the first time housed in a dignified and satisfactory way in the League house at 1102 East Ann Street.”

The house became a social hub for African American students. Numerous notices in The Michigan Daily announced meetings, “get-acquainted” receptions, and other events held at the house. Still, while the house mitigated some African Americans’ social isolation, it was unable to erase the lingering bitterness of exclusion from the much nicer dormitories.

Finally, in 1930, Mosher-Jordan was on the verge of opening and alleviating the unmet housing needs of women students. Housing the approximately 15 African American women on campus, however, remained an unresolved issue.

The Right to Live in Dorms

By the spring of 1930, charges of racism swirled around the new Mosher-Jordan dormitory, even though its doors weren’t officially open. Helen Rhetta of Baltimore and Vivian Wilson of Washington, D.C., had applied for residence in Mosher Jordan in December 1929, but by the end of the school year had not heard any response, despite the fact that white classmates were being accepted into the new space. The Baltimore-Afro American ran a story on September 19, 1931, about Rhetta’s fight to live in the new dorm. The article reported that when she returned to Ann Arbor in the fall of 1930, “she was met at the station by Miss Lloyd and taken to a newly painted 20-room dormitory for colored students only”—the house on East Ann Street.

Activism by Rhetta and others succeeded in opening Mosher-Jordan to all women. In 1931, six African American women applied for rooms. Two of them were accepted. Alice Lloyd reported that one of the two “withdrew for financial reasons,” but that the “other one remained and made a very good adjustment.” That “other one” was E’Dora Morton of Detroit, who would move back into the house on East Ann the following year.

Others would continue to fight for the right to live in dormitories. Elsie Roxborough, the daughter of Charles Roxborough, Michigan’s first African American state senator, was one of the next African American women to live in Mosher-Jordan in 1934. Three years prior, in conjunction with Rhetta’s protests, her father had pushed for an investigation into discrimination at Michigan by introducing a Senate resolution.

The newly opened Mosher-Jordan dormitory, photographed in 1930. HS15700.

A classmate of Roxborough, Jean Blackwell, sought to live in Martha Cook but was rejected, prompting an investigation into discrimination that was also reported in The Baltimore Afro-American on September 1, 1934. Of Alice Lloyd, Blackwell later recalled, “I remember the bigotry of Dean Alice Lloyd. She pretended to be concerned about Negro students and wrote kind letters to parents, but she stood firm in holding the line [against integration of the dorms].”

Much Work Remains

The house on East Ann Street would stand until the summer of 1946, when it was razed to make way for the new Food Service Building to serve the expanding dormitories. The Michigan Alumnus noted in October 1945 that a “League house for women students, owned by the University, is on this half block at the present time, and negotiations are now under way to secure another house to replace this in the present set-up.” That “set-up” for African American students moved to 1136 East Catherine, where it continued until 1954 when it too was razed to make room for new University buildings.

Following the decision in 1950 to house all first-year women in residence halls, discrimination in roommate assignments came to the forefront. In 1955, the Student Government Council’s Human Relations Board took on the prevailing use of “race, religion, or ethnic background” as selection criteria. In spite of the challenge, the allocation of roommates based on race would not end until the late 1950s.

The abolition of the position of Dean of Women in 1962 was a key turning point in the liberalization of housing policies as League houses disappeared along with the in loco parentis doctrine. Activism of the Black Action Movement in 1970 forced serious discussion of the living problems faced by African American students. The need for community space was recognized through the establishment of the William Monroe Trotter House in 1972. Recent discussions about the name and location of the Trotter House serve as a reminder that the situation has improved, but much work remains to be done.